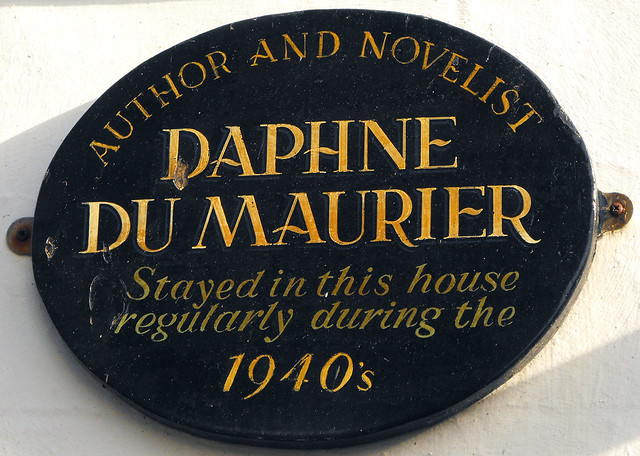

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.

Daphne Du Maurier, Rule Britannia (1972)

Rule Britannia was Du Maurier’s last novel, even though she died two decades later, and a weird mainstream sf effort which the 1970s was to see a few of — John Sutherland calls them As If Nigel’s and that may well do. Imagine a time forty five years ago and the Conservative Party stood in a General Election committing us the join the European Union that hadn’t wanted us as a member a few years earlier. Then imagine an economic crisis in which we are then kicked out, and the U.S. occupy us as protecting force.

That’s the premise of Rule Britannia, told from the perspective of a small town in Cornwall. The town people largely hate the Americans, presumably can’t abide the Europeans and aren’t that enamoured of Londoners.

How things have changed.

I get the sense that an awful lot of British sf up to about 1980 is refighting the Second World War — the plucky islanders, the sense of an ideal fighting for, the blitz spirit and all that. Survivors, Dad’s Army, Secret Army and “Genesis of the the Daleks” are cousins. Du Maurier in Cornwall during the Second World War would have seen the American soldiers stationed around and the local attitudes to them. I suspect the campaign to win hearts and minds — and a quick how’s your father — would have been similar to that in the novel.

The protagonist is Emma, who presumably isn’t interesting enough to narrate but is in every scene even if that takes some jiggery pokery. Her father is a merchant banker of some kind — absent for much of the novel, a vital link to the powers that were — and her grandmother is Mad, a seventy nine year old former actress, inspired by Gertrude Lawrence, Gladys Cooper and, I suspect, du Maurier herself. And then there are various adopted children, under the age of 18, who can be relied on to keep the plot spinning.

Du Maurier had been recruited to the cause of Cornish nationalism and was aware that — as tin mines and fishing declined — the capital’s big economic plan for the West Country was heritage and tourism, until package holidays destroyed even that possibility. This is the occupying U.S.’s vision of Cornwall, with Welsh and Scottish heritage in the mix. A land of surf and Doombar.

There is resistance — although I think the satirical mood here makes the novel step back from the horrors hinted at in the Resistance in The Scapegoat and attempts to pull the wool over the eyes of the authorities. There’s a pompous local MP, a suspicious American colonel (and tougher colleagues), a pliable GP and a mysterious hermit. If this wasn’t a six part BBC drama it should have been — you could easily cast it.

This was a real page turner, not quite the gothic material I’d expect from my limited sense of du Maurier, but certainly worth a read.

There’s only really one Lowry that is immediately recognisable as a Lowry, July, the Seaside (1943), a series of tiny incidents on the beach – games being played, a punch and judy kiosk, sitting, lying, walking, prams, swings. It is the urban crowd transplanted from factory gates and football matches to the sea – possibly in north Wales. What is striking is that the people are dressed much the same – there is no concession to sea and sun. Still, there’s a war on.

There’s only really one Lowry that is immediately recognisable as a Lowry, July, the Seaside (1943), a series of tiny incidents on the beach – games being played, a punch and judy kiosk, sitting, lying, walking, prams, swings. It is the urban crowd transplanted from factory gates and football matches to the sea – possibly in north Wales. What is striking is that the people are dressed much the same – there is no concession to sea and sun. Still, there’s a war on.

There’s also South Shields – Waiting for the Tide (1960) – showing Lowry’s love of solitude and quiteness and isolation. Am I misrecognising A Ship (1965) as Tynemouth?

There’s also South Shields – Waiting for the Tide (1960) – showing Lowry’s love of solitude and quiteness and isolation. Am I misrecognising A Ship (1965) as Tynemouth?  Then, there’s the Self-Portrait as a Pillar in the Sea (1966), awfully phallic. It’s not a surprise to me – do I recall drawn versions of this at Sunderland? There is another painting like this, also 1966, in Sunderland.

Then, there’s the Self-Portrait as a Pillar in the Sea (1966), awfully phallic. It’s not a surprise to me – do I recall drawn versions of this at Sunderland? There is another painting like this, also 1966, in Sunderland. Stand still and look at the flat square.

Stand still and look at the flat square. And from that she got to her curve paintings – some black and white, others using greys, some playing with blue and green and red and grey. Take Cataract 2 (or 3, because I can find a picture of that one) and see how it refuses to lie flat. Cataract 2 is more like an arrow than this – note the stripes aren’t parallel, are offset.

And from that she got to her curve paintings – some black and white, others using greys, some playing with blue and green and red and grey. Take Cataract 2 (or 3, because I can find a picture of that one) and see how it refuses to lie flat. Cataract 2 is more like an arrow than this – note the stripes aren’t parallel, are offset. But they didn’t vanish forever, as in 1997 there was a return. Lagoon 2 widens the vertical stripes and interrupts them, if not with curves then with segments of circles. The vertical lines are further disturbed by diagonals. In the area given to studies, we see variants that led to this and similar designs – trying out colours, rearranging segments, working on graph paper and tracing paper. “Lagoon” points us to something more organic than maths, something away from the abstract.

But they didn’t vanish forever, as in 1997 there was a return. Lagoon 2 widens the vertical stripes and interrupts them, if not with curves then with segments of circles. The vertical lines are further disturbed by diagonals. In the area given to studies, we see variants that led to this and similar designs – trying out colours, rearranging segments, working on graph paper and tracing paper. “Lagoon” points us to something more organic than maths, something away from the abstract. The most recent piece in the exhibition I think (despite that 2014 date) is a wall painting, Rajasthan (2012) – red, orange, green, grey and the white of the wall. There’s not the same sense of the breaking of the plane, but there’s the breaking of the frame. Given what I’m currently reading about the (American?) battle between the wall and the easel, this feels timely.

The most recent piece in the exhibition I think (despite that 2014 date) is a wall painting, Rajasthan (2012) – red, orange, green, grey and the white of the wall. There’s not the same sense of the breaking of the plane, but there’s the breaking of the frame. Given what I’m currently reading about the (American?) battle between the wall and the easel, this feels timely.