Lee Miller: A Woman’s War (Imperial War Museum, London, 15 October 2015-24 April 2016)

Do you know you are not allowed to drink beer in the Imperial War Museum? Or – given that I’m fairly surely they sell it in their café – you are not allowed to drink beer you’ve brought with you in the IWM? Also, I’m pretty sure I’ve seen themed beers in the shop.

I was forced to use a locker for the bottle of Solaris I’d bought for the train home.

I think the last paid exhibition I saw at the Imperial War Museum was Don McCullin – his fantastic war photography. Other photographers, of course, specialise in fashion, or in art, or landscapes or people.

Lee Miller (1907-1977) does art, people, landscape, fashion and war. A rare combination, especially, one might say, for a woman. I’ve seen various exhibitions of her work of late – as if her son Antony Penrose is a man on a mission – most recently her photos of Picasso and her family at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and there’s a vast website at www.leemiller.co.uk. She’s shown up among women surrealists, too.

I don’t think I’d picked up before that she’d been raped as a young child, nor that her father had photographed her in the nude. I recalled nudes of her, including self-portraits, and some of these are on display, along with Paul Homann’s cast of her torso (1939) – an echo of Man Ray’s photo of her – and this suggests an apparent degree of bodily freedom that seems a little odd. Exhibitionism as defence?

She’d worked as a model in New York for Arnold Genthe, George Hoyningen-Huene, Nickolas Muray and Edward Steichen, before going to Europe in 1929 and working with Man Ray as muse, model and photographer. She experimented with the solarisation process – which was also to be used by Barbara Hepworth. On her return to New York in 1932, she set up her own studio, but married wealthy businessman Aziz Eloui Bey and moved to Cairo. Her photography shifted from surrealism to landscape, focusing on the desert and ruined villages in the sands. On a trip to Paris she met the collector and artist Roland Penrose, beginning a long affair with him that would eventually become a marriage. She took photographs in the Balkans, as well as Syria and Egypt, before war broke out.

In theory she should have gone back to the United States, but she had taken a job with British Vogue. Initially she was working as a fashion photographer – it was Vogue, after all – and part of the work was to keep spirits up with the keeping up of standards. But as the war went on, it intruded on the photographs. Models posed in bomb sites or wore gas masks – fashion colliding with surrealism. She took photographs of women in uniforms and doing war work, as well as nurses.

By 1944, she was accredited as a war correspondent for Vogue — there’s an intriguing photograph by David E. Sherman of her in uniform in front of the Vogue cover with a soldier, women and a stars and stripes flag – and she got more involved in the war. The way she tells it, it was almost a lark, but that might be a survivor talking.

She was meant to go to Normandy, after the landings, and to avoid trouble, but she ended up in Saint-Malo, still under German control but heavily shelled by the American army. Unlike other journalists, Miller mixed with and apparently had affairs with the military, and didn’t buckle down to follow the official itinerary. She ended up in liberated Paris – where she photographed fashion shows – and went into Germany. The photographs on display include some of Dachau and Buchenwald, the concentration camps, one being feet in boots, somewhere between a dancer and a fashion shoot. In Munich she entered Hitler’s apartment, Scherman taking a photo of her in Hitler’s bath, nude of course, her muddied boots on the mat, a photo of Hitler on one side, a statuette on the other. It is a grim jest.

That was almost it – she returned to Britain in 1946 and took more photos of Budapest, finally reconciling with and marrying Roland. In 1948, Antony was born; Picasso continued to visit and remained a friend of the family. Miller gave up photography almost entirely – there’s a 1946 photograph of Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning, with Ernst as a giant and she had photos in the 1955 The Family of Man exhibition curated by Steichen at MOMA, New York – in favour of becoming a cordon blue cook and writing about it for British Vogue.

Antony apparently didn’t know about the war photographs until after her death, which seems incredible. Miller was also focusing on helping Roland with his various biographies of artists.

But the body of work is remarkable – black and white, sharp, often square and remarkably well framed. Sometimes the fashion influence is discernible in the reportage, sometimes there is staging, but a dark humour and sense of surrealism often bubbles through. She wasn’t the only female war photographer – the exhibition mentions Margaret Bourke-White (1904-71), who was also with the US Army and had been in the Soviet Union in 1941 when the Germans invaded – but hers remains an impressive body of work.

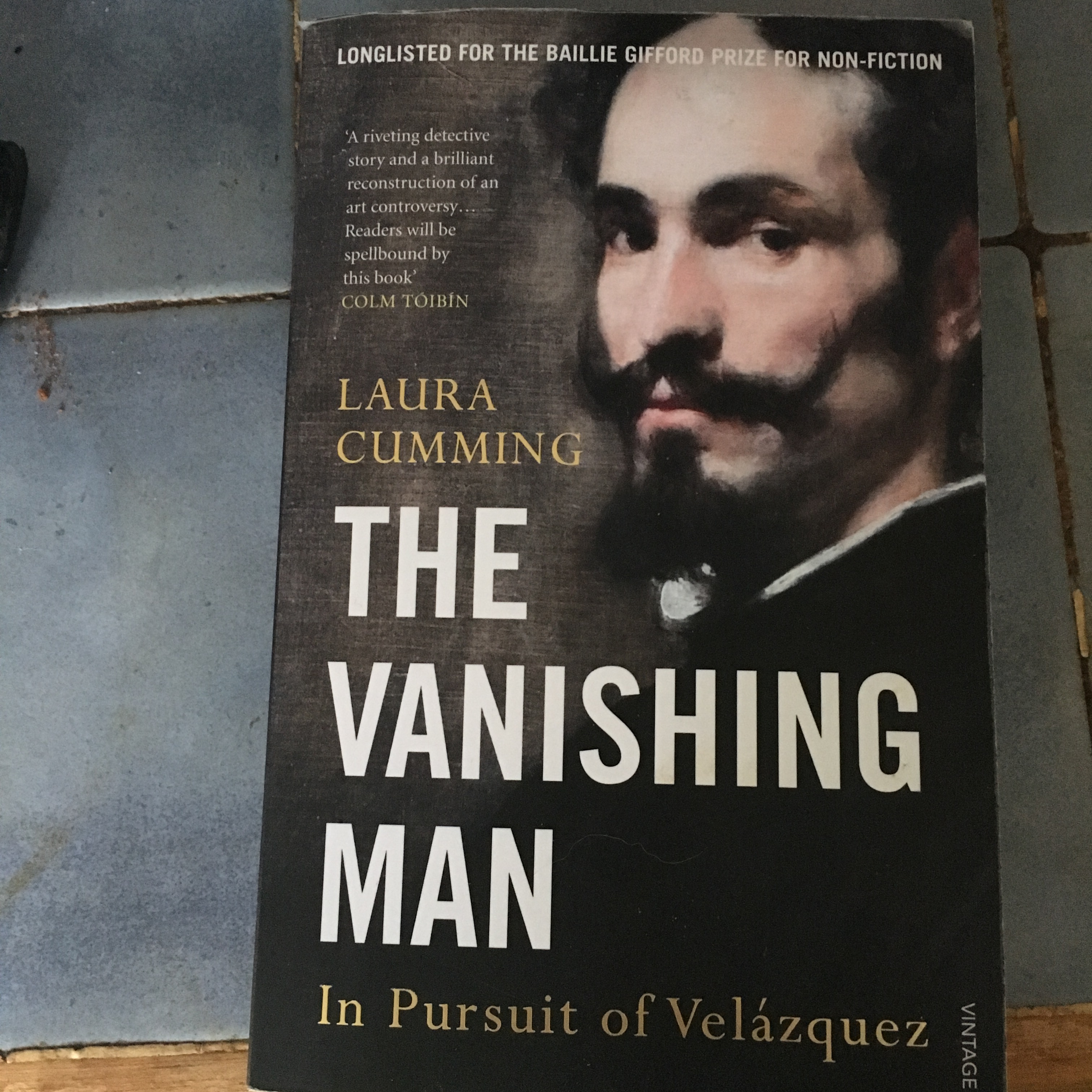

I was browsing the freebie table at Worldcon when I found this and picked it up. I confess that I haven’t much knowledge of Diego Veláquez, a seventeenth century Spanish painter, beyond Las Meninas as inspiration for Picasso and Pope Innocent X as inspiration for Bacon. It seemed to be a book about a single painting — and then I noticed the author was Laura Cumming, art critic for The Observer and author of On Chapel Sands, a biography of her mother’s hidden past.

I was browsing the freebie table at Worldcon when I found this and picked it up. I confess that I haven’t much knowledge of Diego Veláquez, a seventeenth century Spanish painter, beyond Las Meninas as inspiration for Picasso and Pope Innocent X as inspiration for Bacon. It seemed to be a book about a single painting — and then I noticed the author was Laura Cumming, art critic for The Observer and author of On Chapel Sands, a biography of her mother’s hidden past.