Elisabeth Frink: The Presence of Sculpture (Djanogly Gallery, Nottingham Lakeside Arts, 25 November 2015–28 February 2016)

My sculptures of the male figure are both man and mankind. In these two categories are all the sources of all my ideas for the human figure. Man, because I enjoy looking at the male body and this has always given me and probably always will, the impetus and the energy for a purely sensuous approach to sculptural form. I like to watch a man walking and swimming and running and being. I think that my figures of men now say so much more about how a human feels than how he looks anatomically. I can sense in a man’s body a combination of strength and vulnerability — not as weakness but as the capacity to survive through stoicism or passive resistance, or to suffer or feel

Outside Caffè Nerd on Dover Street, just off Piccadilly, is a small equestrian statue, usually with a pigeon on its head. I sat by it a few times before I realised it was an Elisabeth Frink, and I confess that I don’t recall why I began to pay attention to her. There was a small show at Woking I took myself off to a couple of years ago and materials at the Beaux Arts Gallery, London.

Outside Caffè Nerd on Dover Street, just off Piccadilly, is a small equestrian statue, usually with a pigeon on its head. I sat by it a few times before I realised it was an Elisabeth Frink, and I confess that I don’t recall why I began to pay attention to her. There was a small show at Woking I took myself off to a couple of years ago and materials at the Beaux Arts Gallery, London.

In my mental map, British twentieth-century scuplture was dominated by three names — Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Eduardo Paolozzi — before we get into the Caros and the Gormleys and the more conceptual sculptors. Moore and Hepworth seem to occupy a curious middle ground between neoromanticism and modernism — shapes somewhere between the abstract and the bodily, sensual, demanding to be caressed. Paolozzi is plainly of the machine age — the aesthetics of collage and the cyborg, Lego bricks and circuit boards in bronze.

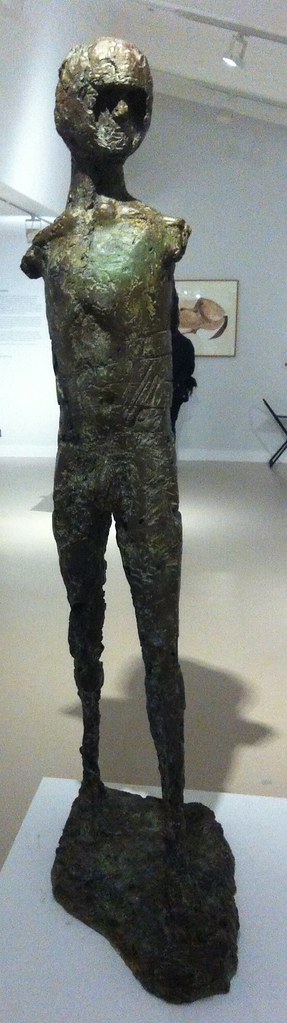

Whilst all three are producers of solid work, Moore and Hepworth are more abstract and Paolozzi is more surreal than Frink. Frink’s sculpture has an extraordinary physicality to it. Her statues are of walking, running, jumping, flying and falling men — yeah, pretty well all men — and clearly there is tension between such movement and the fitness of bronze or concrete. Even the standing men seem to loom, arms behind their back, cock and balls hanging, solid presences, somewhere between threatening and sexualised.

Whilst all three are producers of solid work, Moore and Hepworth are more abstract and Paolozzi is more surreal than Frink. Frink’s sculpture has an extraordinary physicality to it. Her statues are of walking, running, jumping, flying and falling men — yeah, pretty well all men — and clearly there is tension between such movement and the fitness of bronze or concrete. Even the standing men seem to loom, arms behind their back, cock and balls hanging, solid presences, somewhere between threatening and sexualised.

Imagine: some of these were commissioned for the headquarters of W. H. Smiths. Remember that when you try to get your free chocolate bar with a copy of The Mail on Sunday. The Walking Man became one of the Riace, named for the bronze statues found in the sea in 1972, and is in white face, one of Frink’s odd experiments in coloured bronze. Apparently her statue of a dog was coloured; the Desert Quarter (1985) bronze is white. Are these angels or demons?

Imagine: some of these were commissioned for the headquarters of W. H. Smiths. Remember that when you try to get your free chocolate bar with a copy of The Mail on Sunday. The Walking Man became one of the Riace, named for the bronze statues found in the sea in 1972, and is in white face, one of Frink’s odd experiments in coloured bronze. Apparently her statue of a dog was coloured; the Desert Quarter (1985) bronze is white. Are these angels or demons?

She’s presented here in a curiously dialectic way; on the one had she was a child during the Second World War although she knew of the horrors of Belsen and the atomic bombs, the anxieties of the Cold War; on the other hand her public commissions are associated with the Utopianism of the Garden City and New Town movement in the post-war rebuilding. Sculpture was meant to inspire people — whether outside civic buildings or shopping centres, or in the new Coventry and Liverpool Metro Cathedrals.

Her Christ, in a gouache, is muscular, the emphasis on the physicals over the divine. There are pictures here of the crucified Christ, the body emphasised over the cross. There is a Mary and a nun, and a study for Judas, which is also known as the warrior. Her military men — the flying men, the air men — always already seem traumatised, the sculptural equivalent of post-traumatic stress syndrome. And that makes me wonder about her Judas; he betrayed with a kiss, he was paid his thirty pieces of silver, he bought the field and hung himself. Was Judas a warrior — did he fight with his demons and lose?

There is her Birdman, apparently commissioned for a school but thought destroyed (like her first commission, but a damaged version was found this year), a tall, gangly man, with stubs on his back, decommissioned wings perhaps, a fallen angel among men. There is her Running Man (1978), not, apparently, an athlete, but rather a fugitive from some unspecified conflict. Her Flying Men (1982) are hang gliders but seem about to cast themselves into space — inspired by one Léo Valentin (1919-56) who made his own birdlike wings in a vain attempt to fly. Is he also her Falling Man (1961)?

There is her Birdman, apparently commissioned for a school but thought destroyed (like her first commission, but a damaged version was found this year), a tall, gangly man, with stubs on his back, decommissioned wings perhaps, a fallen angel among men. There is her Running Man (1978), not, apparently, an athlete, but rather a fugitive from some unspecified conflict. Her Flying Men (1982) are hang gliders but seem about to cast themselves into space — inspired by one Léo Valentin (1919-56) who made his own birdlike wings in a vain attempt to fly. Is he also her Falling Man (1961)?

There are animals — lots of horses, sometimes with riders, a boar for Harlow, warthogs and dogs. Dogs whose heads you want to pat but mustn’t. There are birds, but of ill omen, her Harbinger Bird III (1961) and Warrior Bird (1953), corvids, menacing; on the other hand her eagles, often designed for pulpits and linked to the Kennedy assassination (there is also an uneasy sculpture, The Assassins, but all of them are uneasy).

There are animals — lots of horses, sometimes with riders, a boar for Harlow, warthogs and dogs. Dogs whose heads you want to pat but mustn’t. There are birds, but of ill omen, her Harbinger Bird III (1961) and Warrior Bird (1953), corvids, menacing; on the other hand her eagles, often designed for pulpits and linked to the Kennedy assassination (there is also an uneasy sculpture, The Assassins, but all of them are uneasy).

And of course, there is the baboon, commissioned for London Zoo, but it’s a different version here. And there’s a water colour, apparently inspired by an Australian trip although that makes little sense, of an encounter between a man and a baboon. Apparently the baboon is unimpressed by the man.

So her subject is man rather than woman. She may have done mother and child pairs like Hepworth and Moore, but none are here on display, and she was clearly a mother. The few female statues here are caped or cowled. Is there an avoidance of female objectification? Is her aim to objectify men? There were warrior women she could have portrayed, traumatised refugees. But clearly that was not for her.