Klimt/Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina (Royal Academy of Arts, 4 November 2018-3 February 2019)

The Albertina Collection was founded in 1776 by Duke Albert of Saxe-Teschen and now has a million drawings and prints, which rarely see the light. Here, marking the joint centenary if their deaths we get a joint exhibition of, well, not quite Master and Pupil, but evidently of two of the leading Austrian artists of the first two decades of the twentieth century. As the medium is drawing, and the fame behind Klimt is for paintings such as The Kiss and we probably know Schiele through his drawings, the younger man will win this draw off.

We see Klimt as a professional, preparing for murals, friezes and paintings, his Studies for Shakespeare’s Theatre (1886) and see such a lot of detail in the lines and shading. There’s his work for Vers Sacrum, associated with the Secession movement he co founded.

The detail and the line feels very different from that which Schiele is to adopt — even in an early Academy piece like Reclining Female Nude (1908) there’s a confidence in the line, with minimal shading the contours are clear, but on the other hand he keeps a context here of sorts that he will lose. We see, just about, the surface she is resting on.

But then Klimt had perhaps moved more in that direction, with the preparatory sketches he was commissioned to do on Jurisprudence, Philosophy and Medicine for University of Vienna buildings. We don’t really get to see the finished items, but these seem Expressionist poses rather than idealised, with a variety of body types. Note his use here of packing paper — was this standard? Was there a surface here suited for black chalk? Is the light brown giving the pictures a desired quality?

Whilst clearly the two met, one famous, the other upcoming, and overlapped in subjects, Schiele was not part of the Secession until Klimt died, when he got to curate the 49th Exhibition in 1918, towards the end of World War One. Schiele’s poster, somewhat expressionist, has an L-shaped table of artists, with a place left for Klimt and himself at the head. No false modesty here.

We get more glimpses of Klimt’s practice here, an Embracing Couple — Study for This Kiss to the Entire World (1901), a preparation for the Beethoven frieze (a nod to “Ode to Joy”) and a variant on The Kiss in Standing Loves (1907-8) in which the two figures merge together and there are dots of colour and gold.

Curiously what looks half finished in Klimt feels complete in Schiele. Take the self-portrait The Cellist (1910) where the lack of cello is striking, but we are drawn by the hands, always vital in his work, and the Frankenstein monster anticipating forehead. And the brightness of the orange and reds. There are two female nudes from the same year, drawn from the front and the rear, limbs lopped off but hands sometimes visible, with a white halo painted around her, a technique he was to repeat in self-portraits. Apparently it’s to do with theosophy. Shrugs.

Are these finished works? Works in their own right? Preparatory for paintings not completed or not seen here?

Alongside here there are flowers and landscapes and fragments of architecture, and a quote from the man “Copying from nature is of no consequence because I paint better from memory than in front of a landscape”. Again, no modesty. The Carinthinian Landscape (1914) repays attention with those simple lines and infill, but is that a figure above? Or a ghost of mountains?

Then the disaster of the arrest, “failing to keep erotic nudes in a sufficiently safe place”. For once he seems to get proper paper and water colours, and we get twisted images of chairs and corridors, I Feel Not Punished But Cleansed (1912), a Van Gogh perspective perhaps. The twisted self portrait of For Art and For My Loved Ones I Will Gladly Endure to the End (1912), lines like blades extending his right hand fingers, almost a death cowl, almost a halo. The loved one is Wally, whom he would be forced to abandon.

Klimt returns, drawing society portraits in search of commissions, almost never full length, oddly cutting off the tops of the ladies’ heads. The Lady with Cape and Hat (1897-98) is the masterpiece, in chalk, much more confident oddly than his lines on the later drawings.

The penultimate section gives us Schiele’s self-portraits, again, and those of family members, his mother, his sister, his wife… and then the extraordinary range of self depictions, culminating in two figures of him squatting, nude, a preparation for a family portrait (with a child who was never born). Klimt, unless we count The Kiss never made a self-portrait. This seems more modest.

But he did work with the erotic, but the lines in the drawings here seem much less confident than Schiele’s, even as he has reclining female nudes with raised legs so that the pubic area is visible. Schiele seems to master the frame, allowing limbs to go beyond the paper’s edge, colouring in lips, nipples, pubic hair, stockings, suspending these figures in mid air as there is no shadow or little shadow of the models marking a ground, there is no context (save, once here, with a rug). The bodies melt together, anticipating the erotic violence of Pablo Picasso. There is a skill in foreshortening or in forming geometric shapes, diagonals and rhomboids.

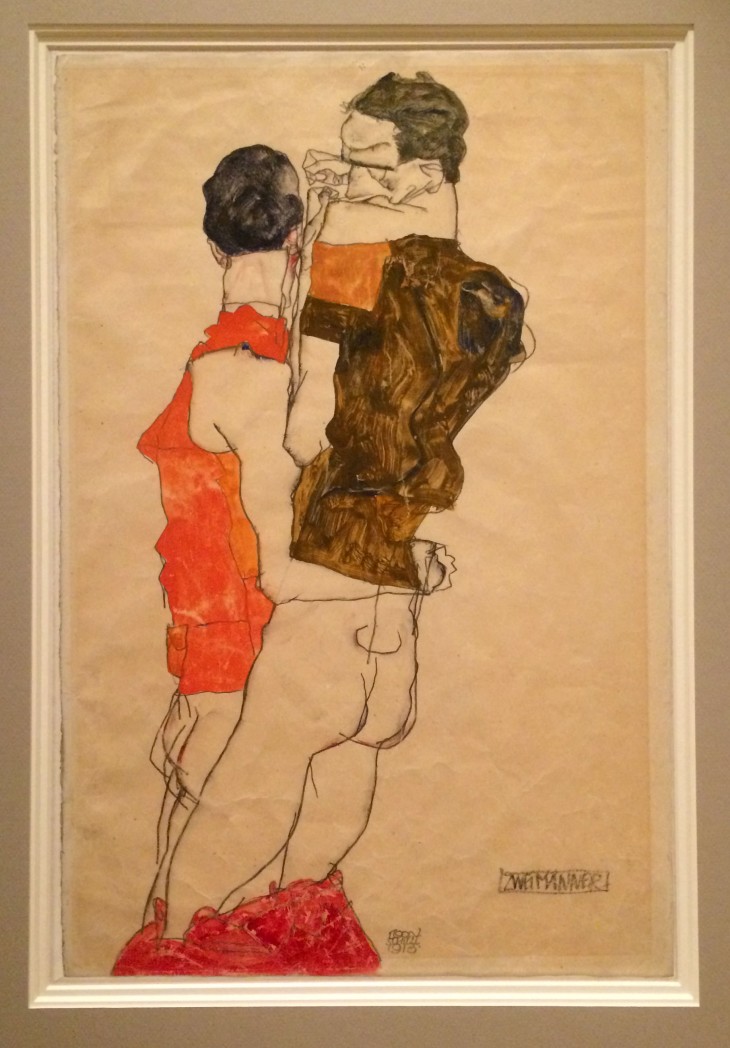

And perhaps most striking, Two Men (1913), two men embracing, one’s head turned away but harder to read the other, whose trousers are around his ankles. Two men? Two gay men? Is one of them Schiele? It wouldn’t surprise me. The female figures look back at us, as if aware, as if challenging us.