Abstract Expressionism (Royal Academy of Arts, September 2016—2 January 2017)

There’s a story that in the late 1940s, the CIA funded Abstract Expressionism. It was an exercise of soft power, from the people who funnelled money into the animated Animal Farm and exploding cigars. The Soviets were busy with their Socialist Realism, whilst the Americans were channelling the chap with the lily pads with bigger brushes. The AES paint big, really big, and it takes a lot to transport all those canvases around the world. In one version the Tate wasn’t able to afford a huge exhibition and an benefactor gave the money. The story is the money came from the CIA.

If Abstract Expressionism didn’t bring down the Berlin Wall, then at least it came up with pretty cool murals.

It’s the sort of thing that can leave you cold, but if you surrender to it it’s pretty amazing.

Just like capitalism.

The cavernous spaces of the Royal Academy seem appropriate, although they’ve never quite got the walk through right. These are huge, abstract paintings, determinedly non-representation, yet in theory expressing an inner emotion. Of course, we don’t always know what that emotion is, but you can always supply your own.

The first room was a kind of overture, showing paintings from many of the big names prior to the glory days. Some of these are portraits, few of them are great, but you can see the roots in Barnett Newman’s green stripes on dark red. There’s a curious Mark Rothko, Gethsemane (1944), presumably alluding to the night of Christ’s betrayal, and sort of cruciform, but it might be an eagle with an American football. And a weird cloud flag.

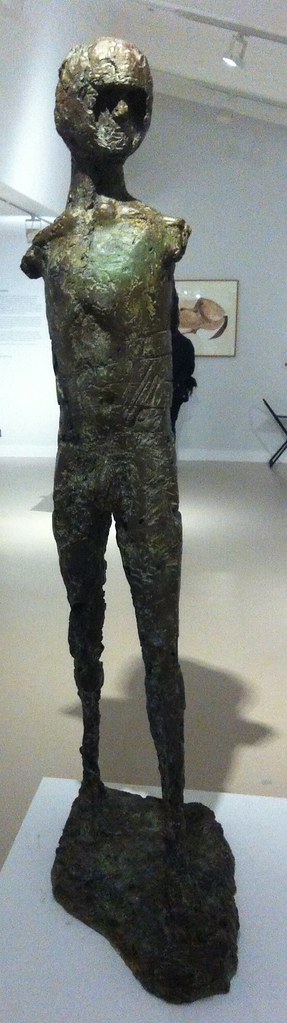

Clyfford’s Still’s PH-726 (1936) has wobbly male and female bodies inscribed within a block — a two dimensional version of what Moore and Epstein were carving at about the same time. A new name to me, I confess, but one I will return to later.

And so the various stars come out — and the rooms which focused on one or two artists were stronger than those which offered dubious thematic arrangements. That being said, I don’t get on with Arshile Gorky, having bounced off his Tate Modern show a few years ago. A numbers of them look like oddly painted figures in a room — say Diary of a Seducer (1947) — and I see I’ve made the note to myself, “bad photoshop”.

Jackson Pollock, on the other hand, is truly sublime. I never quite wrote up all my notes from Liverpool, but the late, black pour, works feel like the figurative abstracted. Like Rorschach tests, you can find the sail boat if you squint right. He gives in to the chaos of the drip, somewhere between randomness, automatic painting and the unconscious at work. There’s a huge mural, designed for Peggy Guggenheim’s New York apartment, with “a prancing, bestial presence” which maybe you wouldn’t want to live with. You don’t get a lot of help from the titles — even Summertime (1948) isn’t that helpful, with its wide, short overlapping of colours and drizzles. The trajectories of flies on a summer’s evening? There’s his Blue Poles (1952), with its striking, vertical totems, daring you to distinguish figure from ground. There are other colours, of course, (black grey white) but it’s striking how often he returns to red, blue and yellow, as if he’s unravelled a Piet Mondrian.

[and there, tucked on one wall, is Lee Krasner, not quite the token woman — though it does have to be said that AE is a very blokey genre with its SIZE DOES MATTER statements in oil — who takes four years to come to terms with Pollock’s stupid death in a car crash, who only then can “wrestle” with his ghost to produce The Eye is the First Circle (1960), which inevitably has to be read as homage and imitation rather than the work of an artist in her own right. Later, we’ll come across Helen Frankenthaler, whose exhibition I missed at the Turner, with Europa (1957) although I saw no bull.]

Mark Rothko is glorious, as always, and the room of his work at Tate Modern can reduce me to tears. As always the paintings seem to ride the walls, rather than be hung on the them, the layers, the laminates of colour lumess and dammit that is a word. You are surrounded by them in an octagonalroom, dwarfed, and I was annoyed to see people taking selfies against them — not because of any objection to such narcissism, but because my instinct is to disappear into these canvas rather than superimpose myself upon them. There are exquisite vertigo.

I don’t think I’ve come across Clyfford Still’s work before, but I’ve put his museum in Denver on my long term to do list (when the US is more sensible about the TSA…). These are vast canvases, representing vast landscapes, abstracted into colours. My favourite was PH247 (1951), also known as Big Blue, a luminous canvas of many blues, interrupted by dark brown and orangish vertical strokes. This, too, is a room to get lost in.

Less successful is Willem de Kooning’s work, here dominated by his paintings of women, of which he wrote “I wanted them to be funny … so I made them satiric and monstrous, like sibyls”. Gee, thanks. These are women as landscapes, rather than in, to my eyes deeply misogynistic. His other landscapes, notably Dark Pond (1948), which I misread as and viewed as Duck Pond, are better, but I don’t feel inclined to follow him up.

The shared rooms were on the whole less successful, with less of a chance to get to know the range of the artists’ work. A few women sneak in here — Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Janet Sobel — and I suspect the only Black artist, Norman Lewis. I wanted to know much more about his work. A room of drawings, books, prints and photographs got a little unruly, as the labels and pictures were not always as clear as they might be in the crowds. The final room gives space to Joan Mitchell’s four huge canvases of Salut Tom, echoing Postimpressionism as much as Abstract Expressionism, and represents late work of some of the big names — although of course Pollock was long since dead.

One final room to draw attention to is the one of Barnett Newman and Ad Rheinhardt, who interrupt swathes of colour with zipped colours or focal zones. Rheinhardt retreated into the Malevich black square for fourteen years — 60″ x 60″ canvases painted all back. The spartan austerity is striking. But Newman was the revelation, and I wonder if he was the inspiration for the Abstract Expressionist Rabo Karabekian’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony in Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions (1973). Eve (1950) is a mostly red canvas with a dark red stripe on the right hand side and its twin Adam (1951-52) is brown with three red stripes of different widths. I have know idea if they connect, but he somehow feeds into Bridget Riley‘s stripes. Newman writes “only those who understand the meta can understand the metaphysical and his paintings are as much their paint as anything else — the rich blues and reds.

Of course, these artists went through a whole range of political experiences from Pearl Harbor to Watergate, and I guess they mark the point when the art world shifts from Paris to New York, with Rauschenberg and Warhol waiting in the wings (and O’Keeffe‘s rather different abstracts predate, postdate and overlap with their heyday). They are, of course, always on the edge of being the emperor’s new clothes, just paint on canvas, randomness. But in the vast spaces of the Royal Academy most of the work transcends that caveat.

Stand still and look at the flat square.

Stand still and look at the flat square. And from that she got to her curve paintings – some black and white, others using greys, some playing with blue and green and red and grey. Take Cataract 2 (or 3, because I can find a picture of that one) and see how it refuses to lie flat. Cataract 2 is more like an arrow than this – note the stripes aren’t parallel, are offset.

And from that she got to her curve paintings – some black and white, others using greys, some playing with blue and green and red and grey. Take Cataract 2 (or 3, because I can find a picture of that one) and see how it refuses to lie flat. Cataract 2 is more like an arrow than this – note the stripes aren’t parallel, are offset. But they didn’t vanish forever, as in 1997 there was a return. Lagoon 2 widens the vertical stripes and interrupts them, if not with curves then with segments of circles. The vertical lines are further disturbed by diagonals. In the area given to studies, we see variants that led to this and similar designs – trying out colours, rearranging segments, working on graph paper and tracing paper. “Lagoon” points us to something more organic than maths, something away from the abstract.

But they didn’t vanish forever, as in 1997 there was a return. Lagoon 2 widens the vertical stripes and interrupts them, if not with curves then with segments of circles. The vertical lines are further disturbed by diagonals. In the area given to studies, we see variants that led to this and similar designs – trying out colours, rearranging segments, working on graph paper and tracing paper. “Lagoon” points us to something more organic than maths, something away from the abstract. The most recent piece in the exhibition I think (despite that 2014 date) is a wall painting, Rajasthan (2012) – red, orange, green, grey and the white of the wall. There’s not the same sense of the breaking of the plane, but there’s the breaking of the frame. Given what I’m currently reading about the (American?) battle between the wall and the easel, this feels timely.

The most recent piece in the exhibition I think (despite that 2014 date) is a wall painting, Rajasthan (2012) – red, orange, green, grey and the white of the wall. There’s not the same sense of the breaking of the plane, but there’s the breaking of the frame. Given what I’m currently reading about the (American?) battle between the wall and the easel, this feels timely.