William Eggleston: Portraits (National Portrait Gallery, 21 July-23 October 2016)

Category / reviews

Never Marry Your Cousin

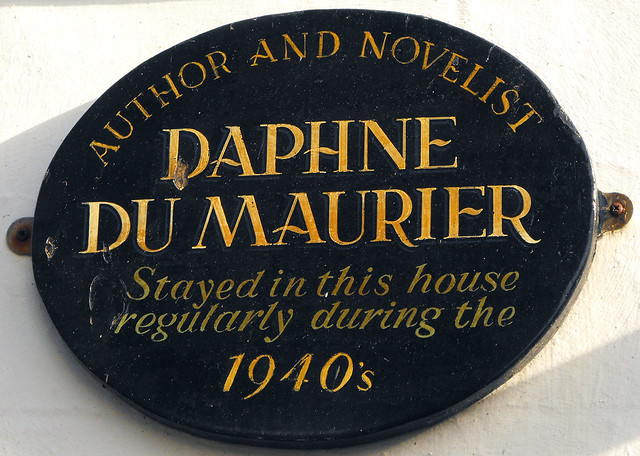

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked another one at random.

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked another one at random.

“This, I suppose, was what men faced when they were married. Slammed doors, and silence.

Dinner alone.”

Daphne Du Maurier, My Cousin Rachel (1951)

Little Orphan Philip lives on a big Cornish estate at some point in time – it’s never entirely clear when, but the lack of trains would put it at some point in the early nineteenth century. His Confirmed Bachelor uncle, Ambrose, fully anticipates that Phil will inherit everything, the lazy brat, but that is before he goes on a holiday to Italy and meets, falls in love with and marries Rachel. Phil’s cousin.

Before you can say, “Cradle snatcher”, it becomes clear that Ambrose is unwell and Philip makes a mad dash across Europe, only to find his uncle dead and his mysterious cousin absent. He returns to Cornwall and begins to run the estate, blind to the sudden charms of the local unmarried women who are awaiting his proposal.

And after a few months he is joined by Rachel – whom at first he is determined to dislike because, yanno, probable homicide, but who he gets a crush on. If there were justice (and she isn’t just an evil schemer), Rachel would get the estate, and Philip seems to do everything he can to give it to her, made complicated by everything being in trust until his twenty-fifth birthday.

What is not clear here, of course, is how reliable the self-serving Philip is. Is it really wise to want to marry a cousin with a dodgy back story? Is it good taste to marry one’s uncle’s widow? Or is Rachel perhaps just poor at handling money and the victim of an infantile young man brought up in a homosocial environment?

The Crow Bridge

“We can’t go to the police, the police are boring. Alfred Hitchcock says so”

— The Beiderbecke Affair

Stonemouth (Charles Martin, 2015)

There’s a sense of deja vu about this Iain Banks narrative — the hulking bridge, the family secret, the huge clan, sex and drugs and violence. I remember being gripped by the television adaptation of The Crow Road nearly twenty years ago and the astonishing performance by Peter Capaldi who deserves to play more great roles. In this two-part television adaptation we have a similar set of tangled relationships in a small Scottish town — at a wedding Stewart Gilmour (Christian Cooke) sees his fiancée Ellie Murston (Charlotte Spencer) kissing someone and then disappears off to a toilet cubicle for a line of coke and a shag. This understandably leads to his being chased out of town. The Murstons are a small time set of gangsters, tartan Sopranos, locked in a rivalry with Mike MacAvett (Gary Lewis), who sells fish even if he doesn’t make people sleep with them. Two years later, Stewart’s best friend Callum Murston (Samuel Robertson) has apparently committed suicide off the Stoun Bridge and Stewart ventures home for the funeral.

Obviously he is taking a risk but the Murstons’ lieutenant Powell (Brian Gleeson) says it’ll be okay, as long he’s gone after the funeral, pays his respects to the Don (Peter Mullan) and keeps away from Ellie. Well, one out of three isn’t bad and without those two there wouldn’t be a plot. Stewart had received a video message from Callum on his mobile before his death and local police officer, old school friend Dougie (Ncuti Gatwa) suggests there is something fishy about the autopsy. Which of the family secrets is the one that either led to Callum being offed or killing himself? And do people really send video messages rather than leave voicemails?

I have to confess that from early on I latched onto gay best friend Ferg (Chris Fulton), who has engaged in shenanigans with a number of people in the town and wondered whether the not-quite-impossible love triangle of Callum-Stewart-Ferg had become possible in Stewart’s absence. The gay gangster is a trope, after all, and usually does not end well. (That might amount to a spoiler, of course. Or a bluff. Or a double bluff.) The plot itself bluffs us and counter bluffs, as it should, with a few moments of ambiguity left for us to question.

Hanging over all of this is the bridge, not quite a refugee from another Banks novel, but quite clearly CGId in, imposed onto the Scottish landscape. Whilst on the one hand let us marvel that tv can do such a thing, on the other it doesn’t seem quite real (in part because we know it isn’t real) and there’s a sense of irreality over the whole. Our Tartan noir has given us Rebus, Brookmyre, Trainspotting, but the contemporary rural Scotland has been Balamory and Hamish Macbeth and Monarch of the Glen. There are a few throwaway lines about Scottish heritage and Presbyterianism, but I can’t quite see the turf wars of the New Jersey bois.

It works because of an extraordinary performance from Mullan as Don — and Banks was clearly winking at us with that name — and a lesser extent from Gleeson. Mullan can do the hardman, but you can see the restrained sorrow and anger at the same time, you can believe there could be a moment of extraordinary violence, you can believe he has the pair of balls he does. If his two surviving sons — referred to as the Chuckle Brothers, and that too must be a trope — were a quarter as hard, then he could put a bid in for Glasgow.

And so Stewart can be menaced but —

— and here we run into the two flaws in the adaptation.

I need to do some thinking about first person or intradiegetic narration. Such a narrator can only tell us what they’ve seen and if, therefore, they die… Well, okay, it’s still possible to narrate whilst drowned in a swimming pool, but not often. But Stewart seems likely to be escaping, er, Scot free, because he’s narrating — although it might not be clear when he’s narrating from. We can only see what Stewart sees — although there are two moments I recall in the first episode where this is broken away from. In the second half of the second episode, even more so. Of course, Blade Runner (1982) is more interesting (if not necessarily better) than the Director’s and Final Cuts because of that narration which gives Deckard ownership of the film and the replicants’ viewpoints. In a novel, it’s easier to mix viewpoints (and Banks does, of course — see Complicity, say); film and tv tends to go for narrow or omniscient. To my mind, the mix is inelegant.

The second flaw is I don’t think Martin can handle those action scenes. I watched the programme on iPlayer and there was something wrong with the streaming as Stewart was chased around the town. Even so, I think there was some slow motion. Indeed, the second episode had a few aspirations to pop video — but it had a great soundtrack so I can see the temptation. But the Chuckle Brothers (who were there in a different guise in Pride) weren’t quite convincing. Stewart was going to have the shit beaten out of him unless he was rescued.

And don’t forget, it has been carefully established that there is a cop in town, who is an old friend of Stewart’s.

I said, don’t forget, it has been carefully established that there is a cop in town, who is an old friend of Stewart’s.

Ah, apparently the script writer did. Or Banks did.

At some point, you go to the police, don’t you?

Spoilers!

I need to read the novel to see whether Banks handles the climax any better. On the one hand, there’s an emotional tug at the heart strings that feels awkward but there’s a move to consolation. It has a choice of two endings: consolation or melodrama. I’m not convinced it picked the right option. I think the Banks of The Wasp Factory would have picked differently.

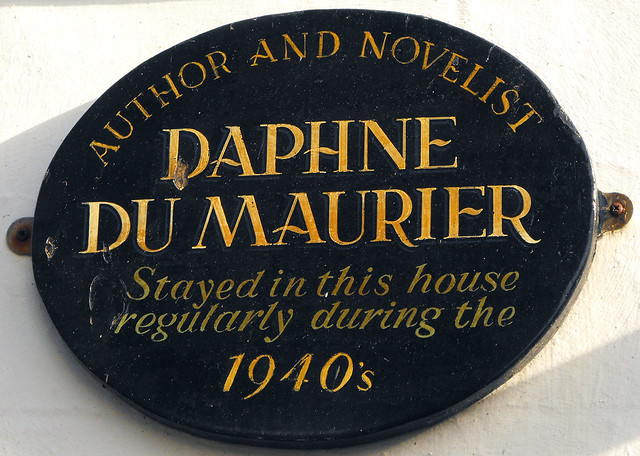

More Majestic Shalt Thou Rise

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.

Daphne Du Maurier, Rule Britannia (1972)

Rule Britannia was Du Maurier’s last novel, even though she died two decades later, and a weird mainstream sf effort which the 1970s was to see a few of — John Sutherland calls them As If Nigel’s and that may well do. Imagine a time forty five years ago and the Conservative Party stood in a General Election committing us the join the European Union that hadn’t wanted us as a member a few years earlier. Then imagine an economic crisis in which we are then kicked out, and the U.S. occupy us as protecting force.

That’s the premise of Rule Britannia, told from the perspective of a small town in Cornwall. The town people largely hate the Americans, presumably can’t abide the Europeans and aren’t that enamoured of Londoners.

How things have changed.

I get the sense that an awful lot of British sf up to about 1980 is refighting the Second World War — the plucky islanders, the sense of an ideal fighting for, the blitz spirit and all that. Survivors, Dad’s Army, Secret Army and “Genesis of the the Daleks” are cousins. Du Maurier in Cornwall during the Second World War would have seen the American soldiers stationed around and the local attitudes to them. I suspect the campaign to win hearts and minds — and a quick how’s your father — would have been similar to that in the novel.

The protagonist is Emma, who presumably isn’t interesting enough to narrate but is in every scene even if that takes some jiggery pokery. Her father is a merchant banker of some kind — absent for much of the novel, a vital link to the powers that were — and her grandmother is Mad, a seventy nine year old former actress, inspired by Gertrude Lawrence, Gladys Cooper and, I suspect, du Maurier herself. And then there are various adopted children, under the age of 18, who can be relied on to keep the plot spinning.

Du Maurier had been recruited to the cause of Cornish nationalism and was aware that — as tin mines and fishing declined — the capital’s big economic plan for the West Country was heritage and tourism, until package holidays destroyed even that possibility. This is the occupying U.S.’s vision of Cornwall, with Welsh and Scottish heritage in the mix. A land of surf and Doombar.

There is resistance — although I think the satirical mood here makes the novel step back from the horrors hinted at in the Resistance in The Scapegoat and attempts to pull the wool over the eyes of the authorities. There’s a pompous local MP, a suspicious American colonel (and tougher colleagues), a pliable GP and a mysterious hermit. If this wasn’t a six part BBC drama it should have been — you could easily cast it.

This was a real page turner, not quite the gothic material I’d expect from my limited sense of du Maurier, but certainly worth a read.

Go West, Young Man

Slow West (John Maclean, 2015)

This is the first Kiwi western.

It may be the first explicitly Darwinist western.

Although I suppose the first label doesn’t quite work on the model of spaghetti westerns. But the landscape, having been out of a job since the fifteenth episode of The Hobbit, gets to play Colorado and so forth. It does it well — and if I get the sense that the same mountains keep appearing, that is only appropriate since there is a dream feel to much of this.

I’ve not been a huge fan of the Western — I guess anxieties about the depiction of First Nations people hovered over them as I was becoming more aware of film and I don’t know enough history to unpick it. I probably need to know more about the American Civil War since so many westerns are set then or thenabouts. I’ve seen a pile of John Ford westerns (The Searchers will be key), Leone’s work, various Eastwoods (not, yet, I think, Unforgiven?) and some made since the turn of the century. The gaps are something I occasionally do something to fill. I don’t recall seeing The Missouri Breaks nor The Hired Hand. But the western is clearly part of the U.S. selfmythologising. There’s much written on it from a structuralist point of view — Sixguns and all that, antinomies, the outsider who expels himself from the society he saves…

So here we have Jay (Kodi Smit-McKee, from The Road), a young son of aristocracy, in search of his not really girlfriend, Rose (Carol Pistorius), on the run from Scotland for crimes that are not her fault. He’s a naïf. He barely needs to shave. And yet somehow — money, lots of it — he has gotten across the Atlantic and out into the West. When he runs into a Unionist officer and two men chasing a Native American, he also runs into Silas (Michael Fassbender) who agrees to help him find Rose.

For a fee.

And that suits Silas, because he wants to find Rose and her father. As indeed do a posse of bounty hunters.

We are offered a string of vignettes of the journey, which curiously lengthens its duration beyond its otherwise economical 84 minutes without out staying its welcome. The editing studiously maintains a right to left movement for our protagonists. We find a trading post, an anthropologist wanting to make his name from studying the native tribes, a group of Black musicians who speak French, a priest with a suspicious case and an old friend with a bottle of absinthe. We also see the skeleton of a pioneered killed by the tree he was chopping down.

Trust no one.

And there are flashbacks to Scotland and stories told around the campfire and meanwhile in Rose-land.

The hut whe she lives looks suspiciously clean even if new, and imported from Inglourious Basterds. Again, there’s something no quite real, as if Jay has conjured this up out of his romantic imagination. We are breaking the rules of narrated cinema — especially when we see a memory related by someone around a campfire that Silas isn’t at. The rules are broken as it veers between comic and tragic, an odd mix of Jarmusch, Coens and Anderson without being arch.

And we build to the generic imperative of High Noon.

There’s a shot at the end of The Searchers where we see out of the door of the house that the girl has been returned to, with Ethan (John Wayne) on the outside, leaving. There’s also a shot here, before a final montage, which rejects that kind of exclusion. The curious paradox of an ending which embraces a family unit being somehow radical — at least in generic terms. Evolution gives us survival of the fittest and Dawkins versions of this add selfish genes. Is there a place in that scheme for selflessness and charity and love? That would be the romantic ending. I think the truth here is murkier — put a foot wrong and you won’t survive. Survival is not a moral act.

This, a debut film from a Scottish musician, is definitely worth your time.

And in the summer that gave us Mad Max and not so feminist dinosaurs, I’d quite like to see Rose’s film.

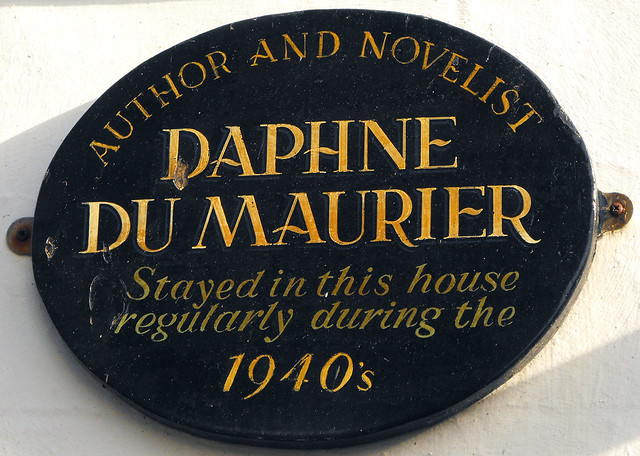

The Secret Scapegoat

Every one of us has his, or her, dark side. Which is to overcome the other?

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. Note “The Birds”, Jamaica Inn and Rebecca. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.

For reasons that escape me, a number of years ago I bought a boxset of Daphne Du Maurier novels. I must have thought this was good plan, because I then bought a second, and a couple of novels not included in either. I also bought the collection which contains the story that was the basis for ‘Don’t Look Now’. Note “The Birds”, Jamaica Inn and Rebecca. The most Hitchcockian of novelists – with perhaps the thought that Du Maurier was a Cornish Patricia Highsmith. The grand plan, being anal, was to read the novels in chronological order of publication, but that never happened and the boxes sat by my bed, gathering dust. So I picked one at random.  Daphne Du Maurier, The Scapegoat (1957) John, a university lecturer, is on holiday in France, fantasising about the past and Joan of Arc, and imagining a secret life. He runs into his exact double, Jean de Gué, and the two go for a drink, in fact a series of drinks, before retiring to de Gué’s hotel room where John passes out. He wakes, in Jean de Gué’s clothes and is mistaken for the other – a Comte who has failed to negotiate favourable terms for the family glass foundry business, who has a morphine addicted mother, who hates (and is hated by) his brother and who is shagging half the female population of the locality. Rather than saying, Oh my good man, you have mistaken me for someone else, to the chaffeur, John decides to take over de Gué’s life and set about saving the family and the business. We are in melodrama territory – the morphine mum, the swooning pregnant wife, the visionary daughter who is on the one hand disappointed by her lying daddy and on the other hand prepared to lie for him. (There is an incident quite late on, a suspicious death that the daughter alibis as accidental.) It feels curiously nineteenth century – but we are in France and we are in the decade after the Second World War and neither detail is irrelevant. The mechanisms of plot are perhaps a little too visible – and one expects the first Mmme de Gué to burn down the chateau at some point… Note that John is given no surname (remember the central character of Rebecca is nameless), and that we can but wonder if he is a doppelganger or the same person, a psychotic twin (or unpsychotic), the result of some trauma. Is John Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? I was careful to avoid spoilers whilst reading the novel and avoided the introduction. What I did discover was that it has been filmed twice, once in 2012 with Matthew Rhys directed by Charles Sturridge and previously with Alec Guinness directed by Robert Hamer. Now that is a film I do want to track down – Guinness is perfects casting (and it’s a bit Graham Greene territory as a novel) and Hamer is better known for Kind Hearts and Coronets, with several Alec Guinnesses. Betty Davies plays the matriarch, which also seems like genius casting. And so I’m tempted to have another lucky dip, another Du Maurier.

Daphne Du Maurier, The Scapegoat (1957) John, a university lecturer, is on holiday in France, fantasising about the past and Joan of Arc, and imagining a secret life. He runs into his exact double, Jean de Gué, and the two go for a drink, in fact a series of drinks, before retiring to de Gué’s hotel room where John passes out. He wakes, in Jean de Gué’s clothes and is mistaken for the other – a Comte who has failed to negotiate favourable terms for the family glass foundry business, who has a morphine addicted mother, who hates (and is hated by) his brother and who is shagging half the female population of the locality. Rather than saying, Oh my good man, you have mistaken me for someone else, to the chaffeur, John decides to take over de Gué’s life and set about saving the family and the business. We are in melodrama territory – the morphine mum, the swooning pregnant wife, the visionary daughter who is on the one hand disappointed by her lying daddy and on the other hand prepared to lie for him. (There is an incident quite late on, a suspicious death that the daughter alibis as accidental.) It feels curiously nineteenth century – but we are in France and we are in the decade after the Second World War and neither detail is irrelevant. The mechanisms of plot are perhaps a little too visible – and one expects the first Mmme de Gué to burn down the chateau at some point… Note that John is given no surname (remember the central character of Rebecca is nameless), and that we can but wonder if he is a doppelganger or the same person, a psychotic twin (or unpsychotic), the result of some trauma. Is John Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? I was careful to avoid spoilers whilst reading the novel and avoided the introduction. What I did discover was that it has been filmed twice, once in 2012 with Matthew Rhys directed by Charles Sturridge and previously with Alec Guinness directed by Robert Hamer. Now that is a film I do want to track down – Guinness is perfects casting (and it’s a bit Graham Greene territory as a novel) and Hamer is better known for Kind Hearts and Coronets, with several Alec Guinnesses. Betty Davies plays the matriarch, which also seems like genius casting. And so I’m tempted to have another lucky dip, another Du Maurier.

Point and Break

Queen and Country (John Boorman, 2014)

And way back in 1987, John Boorman directed an autobiographical film which was a loving portrayal about living through the Second World War, Hope and Glory. I remember rich reds and oranges and sunsets and barrage ballons and the occasional bombsite. Nearly thirty years on, we see the celebration of the child at his schools having been bombed, before cutting to a decade later and life on an idyllic island on the Thames as a prelude to being conscripted into the British army.

It is 1952 and the British are fighting Korea (as part of the communism vs capitalism war) and the old king, who never wanted to be a king, is dying; Elizabeth is going to be crowned and the new Elizabethan Age is dawning. Alter ego Bill Rohan (Callum Turner) meets new BFF Percy (Caleb Landry Jones, who I think gets top billing) and both get put in charge of the typing school and briefing the new recruits. Life is made unbearable by stickler Bradley (David Thewlis) and bearable by shirker Redmond (Pat Shortt) – and the whole film is made bearable by Major Cross (Richard E. Grant).

Is that damning enough?

And there’s girls, glimpsed at a cinema, nurses, and the One, Orphelia (Tamsin Egerton), whom Rohan falls head over heels with despite the large warning light over her head (and the fact that she does get to talk sense about how men treat women in the period whilst still being damaged goods).

I guess this is all very mythic and there’s that whole generation of writers and directors too young for the (Second World) war who did national service and had Sensibilities Formed; some went to to private school, others failed the eleven plus, they’re all eighty or above now, if they’re still alive. If asked, I think I might have assumed that Boorman had died at some point.

The film’s conflicted; on the one hand grandfather despairs about the shame that Rohan has brought on the family, on the other I seem to recall it’s him who gets to dismiss the first Elizabeth. And Rohan is a cipher – neither communist nor capitalist, neither really betraying or supporting others, not quite seduced by his sister, not quite clear what he believes in (besides what he reads in The Times). He is, I fear, the least interesting character in the film. You wonder how Korea itself is going to be handled – an early sequence is not promising – and you slowly realise that virtually everyone over 25 has some kind of PTSD. But there’s just enough gentle comedy not to despair.

I doubt there will be a quarter century gap before this is turned into a trilogy – but I’m assuming a third film about joining the movie industry is envisaged, Pearl and Dean, say. Fun with the Dave Clarke Five. Dealing with Lee Marvin. Buggery in the woods. And Sean Connery in leather shorts.

Abstract Goes the Easel

A Marriage of Styles: Pop to Abstraction (Mascalls Gallery, Paddock Wood, Kent, 28 March-6 June 2015)

This is, ish, very ish, the fiftieth anniversary of the second wave of British Pop Art and the University of Kent, and so Pop Art has decided to mark this by having three universities.

Ah, sorry, my mistake, the University of Kent have three exhibitions – one on campus, which I presume they didn’t feel the need to tell anyone about as I missed it, one on Paolozzi and Tony Ray-Jones, which I’ve written about for Foundation, and A Marriage of Styles at Mascalls Gallery. This gallery has a rather good exhibition policy, but it is a l-o-n-g mile’s walk from Paddock Wood station (thankfully on the flat) and is at a school, so I’ve not been as often as I’ve wanted to. I caught this show on the penultimate day and I’m so glad I did. I should note, also, that there are current two rooms at Tate Modern specifically devoted to Pop Art, even though you’d think that would be at Britain?

So what is Pop Art? Well, the word Pop was used in a slide by Eduardo Paolozzi at his presentation Bunk! at the inaugural meeting of the Independent Group in 1952 and Lawrence Alloway in 1958 was to apply it to art that drew on the visual language of advertising, comic books and everyday life, breaking down boundaries between high and low art. In the US, you’d put Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, who clearly pointed the way for the next generation of British artists, who were mostly at art college in the early 1960s. But if Pop Art constructs a reality through actual or implied collage, these artists were also influenced by more abstract, non-representational, images.

The Paddock Wood show had eleven paintings – I’m guessing one for each member of the the 1966 English worldcup football team – in its two rooms, mostly one to a wall. I’m going to talk about them one by one, mostly from my notes scribbled in the gallery. Continue reading →

28 Dogs Later

“Dogs are not an alibi for other themes [… C]ontrary to lots of dangerous and unethical projection in the Western world that make domestic canines into furry children, dogs are not about oneself. Indeed, that is the beauty of dogs.”

Fehér isten (White God (Kornél Mundruczó, 2014))

I was thrown at first by the nature of the dogastrophe. If we are indeed post-adogalypse, would the headlights on the abandoned car still be on? Would the traffic lights still work?

But still, a pleasingly deserted town, a girl (Zsófia Psotta) cycling in a blue hoodie on the motorway and then a pack of mixed breed dogs chasing her through the streets towards and beyond Aldi.

Flashback.

Dániel (Sándor Zsótér), a former professor (of what?) is inspecting an abattoir (gruesome) and then takes on his daughter (the girl, Lili) and her dog Hagen (Luke and Body, effortlessly doubling) as his ex-wife and her mother heads to Sydney for a conference. Dogs aren’t welcome in the apartment and the dogcatcher (Robert Helpmann Gergely Bánki) soon turns up. The conductor of the orchestra Lili plays in is even less sympathetic. Before you know it, Hagen is abandoned by the roadside. Whilst Lili does search for Hagen, she mainly descends into sex (ish) and drugs and rock’n’roll (or house stuff). Hagen has to avoid the dogcatcher and certain death, but falls instead into the murky world of dog fights and training for them (stop humming the Rocky theme at the back) and is renamed Max. And just when you think he’s hit rock bottom, there is dogalution.

Mad Max: Furry Road.

Oh, please yourselves.

I think I could have lived without the human sections — not that Psotta, Zsótér and others don’t put in fine performances, but it was largely handheld in a shakycam. It veered between the dystopian and the soapian. Ah, but the dog narrative — more Steadicam — did hold my interest, and I presume that soon there will be an American remake with Russell Crowe as Hagen:

My name is Maximus Dogious Magyarus, commander of the Hounds of the North, General of the Canine Packs and loyal servant to the TRUE owner, Lili. Son to a neutered Alsatian, husband to a murdered pooch. And I will have my vengeance, in this life or the next.

Hagen, it turns out, is a legendary Burgundian hero, who shows up in Wagner’s Gotterdammerung, and his Tannhäuser becomes a plot point late on. Redemption through love.

Or games of fetch.

Inevitably there is the whiff of allegory and mettaffa — Mundruczó has spoken about the backlash against immigrants, there’s an anti-gypsy/Romany thread running through and the dog shelter with chimneys had a prisoner of war/concentration camp vibe. I had a sense of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (J. Lee Thompson, 1972), although as with that mythos you worry about the political implications of arguing that gorillas “are” Blacks and so forth.

I suspect, however, there is at the end a sense that Donna Haraway would be a way to unlock this film — a sense of not quite supplication, but mutual supplication. It’s not a comfortable film to watch — although the cast outacted Channing Tatum — and I confess I am ambivalent about dogs. I could have done without being handed a certain flier:

The Stoppard Problem

To ask the hard question is simple:

Asked at a meeting

With the simple glance of acquaintance

To what these go

And how these do;

To ask the hard question is simple,

The simple act of the confused will.

The Hard Problem (2015; writer Tom Stoppard, director Nicholas Hytner, Dorfman Theatre, Royal National Theatre, London, via cinema relay)

For weeks I thought that “the hard problem” was a quotation. But I’m pretty sure I was confusing it in my head with “the hard question”. The hard problem is the problem of consciousness — what is it, where does it comes from, can it be created?

Stoppard has always been a writer of ideas — the talk of chance and probability in Rosencrantz and Guildernstern Are Dead, all kinds of philosophy in Jumpers, the coincidence of Joyce, Lenin and Tzara in Zurich in 1915 in Travesties, quantum mechanics in Hapgood and chaos theory in Arcadia. The recurrent accusation — beyond being too clever for his own good — is that alongside the philosophising and the theatrical gymnastics, Stoppard forgets to have a heart. Well, The Real Thing should have put paid to that.

The Hard Problem is the first Stoppard play I’ve seen since Arcadia; wrong places, wrong times. It’s his first play in years and I don’t think, alas, it’s vintage.

Loughborough University student Hilary (Olivia Vinall) is seeking advice from her lecturer Spike (Damien Molony) as she is applying for a job at the Krohl Institute for Brain Science. He questions her notions of altruism and good and is on the egotism/selfish gene side of human behaviour, especially when she reveals she prays. She gets the job — over a better mathematician, Amal (Parth Thakerar), who goes on to work for the hedge fund run by Krohl (Anthony Calf) which funds the institute — and climbs the greasy pole of research with or without ethics.

In this play, Stoppard is like those fan wank writers who make you feel intelligent. You know, like that episode of Sherlock that invents an underground station so we can be smug about knowing about “The Great Rat of Sumatra” (some people just aren’t ready). The film that preceded the screening had Rufus Sewell telling us how he felt more intelligent when performing in Arcadia. Stoppard begins the play by having Spike explain the prisoner’s dilemma — to be fair, Hilary is bored with how pedestrian that is — and before you know it (well, half a dozen scenes later), Hilary is faced with a situation where she can protest her innocence or claim guilt. Just like a prisoner’s dilemma. Spike tells us that there is no such thing as coincidence — but Hilary runs into an old friend from school, runs into Amal’s girlfriend, runs into Spike in Venice.

Small world.

Still, we never note all those times that someone doesn’t ring us just as we’re thinking of them.

That reunion allows the revelation about Hilary’s past that might lead to a coincidence or not. There was an audible gasp in the audience when that finally panned out. Audiences can be slow.

The problem for me — beyond an age-old wishing for funnier comedies — is that the play was not really about consciousness in any interesting way. There’s a few speeches where we speculate whether human beings are more complicated thermostats…

It’s Daniel Dennett territory:

There is no magic moment in the transition from a simple thermostat to a system that really has an internal representation of the world around it. The thermostat has a minimally demanding representation of the world, fancier thermostats have more demanding representations of the world, fancier robots for helping around the house would have still more demanding representations of the world. Finally you reach us.

And we get a version of the Chinese Box problems, so Searle’s in the mix, too. And that thing about bats is a reference to Nagel.

But this is sleight of hand.

In Hapgood, Stoppard paired idea with theatrical metaphor by asking if a quantum physicist was a spy or a double agent — you could never tell until you looked. I had no sense that the problem of consciousness was being performed here. No moment when Hilary is deluded that she’s conscious, or can’t trust her sense data or is a thermostat.

Instead, the issue is altruism vs egotism — is the good deed still a good deed if it’s for personal gain? Why did that person bring Hilary a cup of coffee? How many times will Spike offer Hilary a lift home in hopes of sex before he gives up? The market that funds the institute is notoriously unpredictable even though the equations of chaos have had a go, and I’m not clear when the play is meant to be set so we don’t have the spectre of 2008 to negotiate. Krohl is ruthless and the game is rigged in his favour — but he also seems a reasonable father. Is his institute altruism or egotism?

But Stoppard has here not worked hard enough to dramatise the speeches, with many scenes as two handers, and doesn’t seem to have the social comedy skills of Ayckbourn anymore to make some of the human interactions painfully, squirmingly funny. The game seems rigged in favour of Hilary — for the female characters in general — and against Spike. Vinall may be the better actor than Molony perhaps, as he is called upon to be eye candy and has a bit of a wandering accent.

And yet — and this is difficult to give full weight to without straying into spoiler territory — a small gesture toward Hilary at the end of the play (which tips the scales to altruism) is genuinely moving. There is a time for altruism and a time for egotism, or they are the same thing, plus time, but I’m not convinced we get any closer to solving the hard problem that way.