In using the myth, in manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity, Mr. Joyce is pursuing a method which others must pursue after him. They will not be imitators, any more than the scientist who uses the discoveries of an Einstein in pursuing his own, independent, further investigations. It is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history. […] Instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method. It is, I seriously believe, a step toward making the modern world possible for art”

The Mythic Method: Classicism in British Art 1920-1950 (Pallant House, 28 October 2016-19 February 2017)

Occasionally I feel as if I should have done some homework before seeing an exhibition.

I will have read, I’m sure, “”ULYSSES, ORDER, AND MYTH” by T.S. Eliot back in the day, 1988 or 1989, and so would have once been aware of the tension between Classicism and Romanticism, and Modernism’s fight against the Victorians. Ulysses appears to the unwary reader a chaotic work, but if anything it is over structured, with bodily organs and literary styles and of course the narrative of the Odyssey. We have a dialectic tension between bringing an archetypal tale up to date and raising a wandering Jew and a wandering poet to the level of classical heroes.

The Pallant, a gallery of which I thoroughly approve down to hours of train timetable research to get there, has a thesis here of British art adopting what Eliot calls the mythical method in the aftermath of the First World War. The attempt is to present the contemporary, the up to date, through a classical lens. Perhaps it is a clutching at order in the ruins of the British Empire. We had had all the isms — Futurism, Vorticism, Cubism — and then a move from the abstract back into the representational. Compare, say, the early work of David Bomberg (who is missing from here) to his post war work.

It is a good story.

Take John Armstrong’s GPO Pheidippides, one of a series of posters advertising the GPO using historical narratives, here the runner who brought news of a battle to Sparta. The athlete is central, between images of male soldiers and waiting women. The image is meant to be of a Greek urn, but there is no attempt at perspective here. Telecommunications with the kudos of myth.

Or Meredith Frampton’s curious Still Life (1932), a hyperreal, photorealistic and yet surreal account of a broken urn on a plinth, alongside masonry and a sculpted head, sawn and shattered trees, flowers, barley and a tape measure. It is a Ozymandian, fallen world, highly suggestive of … hmmm.

And we have more evidently classical subjects — the Vanessa Bell and Duncan Wood Toilet of Venus (a pudgy Venus among the orange and yellow and pink), William Roberts’s The Judgement of Paris (1933) (where the trousered Paris guards his golden apple from a dog) and Roberts’s Parson’s Pleasure (a classical image of donnish nudity on the banks of the Cherwell, with dog paw like trees — and a nod to Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe).

The second room has one of my favourite painters — Edward Burra, with Arcadia, a satire perhaps of the Bright Young Things of the Waugh generation, some in fancy dress, some in berets, over the top male nude statues,cross dressers, and even the staircases in the ornamental garden setting seem voluptuous (Pallant is all too coy, alas). And a little dog steals the show. The other stand out pieces here are again John Armstrongs, as if they wanted a show on him but couldn’t get enough, Psyche Crossing the Styx (1927); Psyche is here a figure from Munch, the rowers fleshy skeletons and the setting seems like it in an interior bodily space. In the Wings (1930) mixes a bust and body parts in a Angus Calder like set of mobiles and wire frames.

The third room offers portraits, by both Proctors, by Frampton again, and more strikingly Gerald Leslie Brockhurst. Here we have Wallis, Duchess of Windsor, described as a contemporary Mona Lisa but with a less enigmatic grin. The flawless depiction, three quarter length, was evidently a piece of propaganda, hard to see now without the unease of eighty years of further royal history and what we think we know about Windsor sympathies. The painting must just predate the Second World War as it is 1939. Meanwhile there is an air about the other portraits of Magritte — indeed many of the paintings on show seem to be edging towards the suburban surreal.

The penultimate room is dominated by photos and a second Burra. The photographs are almost all by Madame Yevonde, working name of Yevonde Cumbers Middleton, with subjects somewhere between art and fashion, in stunning colours. She takes a series of wives of famous men — and each of them is labelled Mrs Famous Man — and dresses them as a classical goddess or figure. Mrs Bryan Guinness, for example, is better known as Diana Mitford, who was to marry Oswald Mosley at Goebbels’s house with Hitler in attendance. At around the same time, Leni Riefenstahl was using classical imagery to dangerous effect; it should be noted that the bleached ruins of Armstrong’s Pro Patria (1938) are anti-fascist in tone.

The Burra is Santa Maria in Aracolei balances several storeys of a building and windows — one with green curtains and a face — with a strange, Daliesque statue with a oddly human hand and a shirt of … feathers? Between the two halves is a staircase, which seems to have a real world equivalent although apparent Burra hadn’t visited the site. Like Burra’s other paintings it is a water colour, in this case on four sheets of paper. It nicely echoes Edith Rimmington’s double portrait of Athena, Sisters of Anarchy in which one of two statues of Athena is turning into an owl. I’d just come across the name at Sussex Modernism, where Rimmington is presented as a photographer.

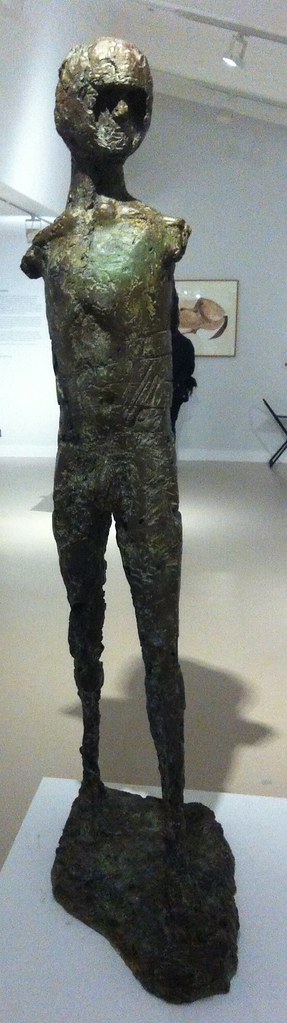

I don’t seem to have made many notes in the final room — I think there was something by David Jones, a name to which I will return — but the stand out piece was Frank Runacres’s Untitled (Ruins) (1939) where works of art, sculpture, wheels, frames and other rubble seem precariously piled over a woman, her head on hand. The bombing of Spain had already happened, but this seems to be looking ahead to the blitz. And in a corner, two small pieces by Henry Moore, one a reclining figure in bronze, but with atypical drapery.

And so we have an interesting narrative, although that one Jones and a single Eric Gill piece point to a counter narrative that could also be told: artists of the period also drew on Biblical narratives, although I would admit the mythic points more to the work of Ravilious, Wadsworth, Nash and other English Romantic Surrealists. Don’t forget Christopher Wood, however, nor Stanley Spencer, probably superior to any of the works on display here.

And if you go back to the PreRaphaelites you can see an equivocation between the mythic and Biblical, but with much more denial of the contemporary in complex ways.

And so, the method is, methinks, a tendency, among other tendencies, but no less interesting for that.